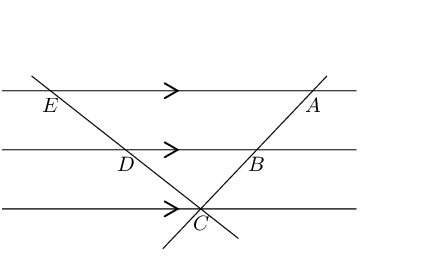

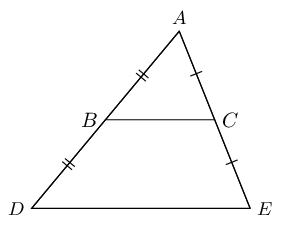

We are given that \(ED: DC = 4:6\), which we can write as a fraction and simplify:

\begin{align*} \frac{ED}{DC} &= \frac{4}{6} \\ &= \frac{2}{3} \\ & \\ \text{And } \frac{ED}{DC} &= \frac{AB}{BC} \\ \frac{AB}{BC} &= \frac{2}{3} \\ \therefore \frac{BC}{AB} &= \frac{3}{2} \end{align*}8.4 Triangles

|

Previous

8.3 Polygons

|

Next

8.5 Similarity

|

8.4 Triangles (EMCJB)

Proportionality of triangles (EMCJC)

-

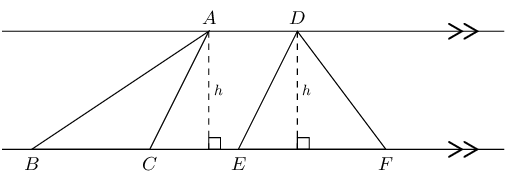

In the diagram below, \(\triangle ABC\) and \(\triangle DEF\) have the same height \((h)\) since both triangles are between the same parallel lines.

Triangles with equal heights have areas which are proportional to their bases.

-

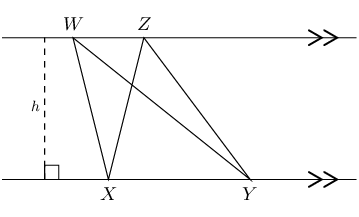

\(\triangle WXY\) and \(\triangle ZXY\) have the same base \((XY)\) and the same height \((h)\) since both triangles lie between the same parallel lines.

Triangles with equal bases and between the same parallel lines are equal in area.

-

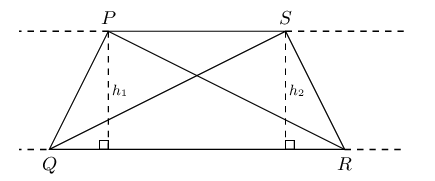

\(\triangle PQR\) and \(\triangle SQR\) have the same base \((QR)\) and are equal in area.

Triangles on the same side of the same base and equal in area, lie between parallel lines.

Worked example 2: Proportionality of triangles

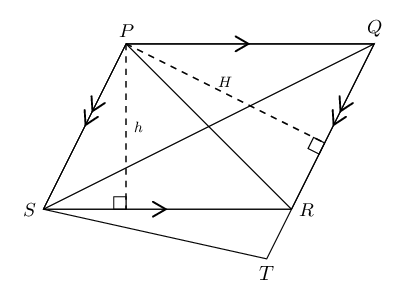

Given parallelogram \(PQRS\) with \(QR\) produced to \(T\). \(RS = \text{45}\text{ cm}\), \(QR = \text{30}\text{ cm}\) and \(h = \text{10}\text{ cm}\).

- Calculate \(H\).

-

If \(TR:TQ = 1:4\), show that \(\frac{\text{Area } \triangle STR}{\text{Area } \triangle PRQ} = \frac{1}{3}\).

Determine the length of \(H\)

We use the formula for area of a parallelogram to calculate \(H\).

\begin{align*} \text{Area } PQRS &= SR \times h \\ &= 45 \times 10 \\ &= \text{450}\text{ cm$^{2}$} \\ & \\ \text{Area } PQRS &= QR \times H \\ 450 &= 30 \times H \\ \therefore H &= \text{15}\text{ cm} \end{align*}Use proportionality to show that \(\frac{\text{Area } \triangle STR}{\text{Area } \triangle PRQ} = \frac{1}{3}\)

We are given the ratio \(TR:TQ = 1:4\).

\begin{align*} \frac{TR}{TQ} &= \frac{1}{4} \\ \text{So then } \frac{RQ}{TQ} &= \frac{3}{4} \\ \text{And } \frac{TR}{RQ} &= \frac{TR}{TQ} \times \frac{TQ}{RQ} \\ &= \frac{1}{4} \times \frac{4}{3} \\ &= \frac{1}{3} \end{align*}\begin{align*} \text{Area } \triangle STR &= \frac{1}{2} TR \times H \quad (PS \parallel QT, \text{ equal heights}) \\ \text{Area } \triangle PRQ &= \frac{1}{2} RQ \times H \\ & \\ \therefore \frac{\text{Area } \triangle STR}{\text{Area } \triangle PRQ} &= \frac{\frac{1}{2} TR \times H}{\frac{1}{2} RQ \times H} \\ &= \frac{TR}{RQ} \\ &= \frac{1}{3} \end{align*}Proportionality of triangles

The diagram below shows three parallel lines cut by two transversals \(EC\) and \(AC\) such that \(ED: DC = 4:6\).

Determine:

We cannot determine the length of \(ED\) since we do not know the lengths of \(DC\), or \(EC\). We only know that \(\frac{ED}{EC} = \frac{2}{5}\).

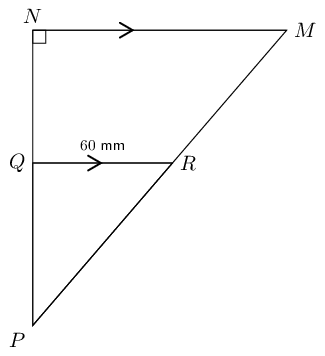

In right-angled \(\triangle MNP\), \(QR\) is drawn parallel to \(NM\), with \(R\) the mid-point of \(MP\). \(NP = \text{16}\text{ cm}\) and \(RQ = \text{60}\text{ mm}\). Determine \(QP\) and \(RP\).

Use the theorem of Pythagoras to determine \(RP\).

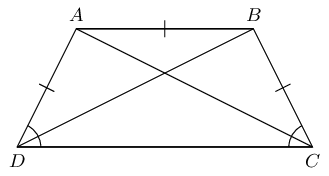

\begin{align*} \text{In } \triangle RQP: \quad PR^{2} &= QR^{2} + QP^{2} \\ &= (8)^{2} + (6)^{2} \\ &= 64 + 36 \\ &= 100 \\ \therefore PR &= \text{10}\text{ cm} \end{align*}Given trapezium \(ABCD\) with \(DA = AB = BC\) and \(A\hat{D}C = B\hat{C}D\).

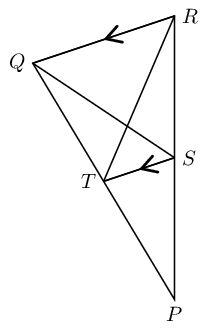

In the diagram below, \(\triangle PQR\) is given with \(QR \parallel TS\).

Show that area \(\triangle PQS = \text{ area } \triangle PRT\).

In Grade \(\text{10}\) we proved the mid-point theorem using congruent triangles.

Complete the following statement of the mid-point theorem:

"The line joining \(\ldots \ldots\) of a triangle is \(\ldots \ldots\) to the third side and equal to \(\ldots \ldots\)"

"The line joining the mid-points of two sides of a triangle is parallel to the third side and equal to half the length of the third side."

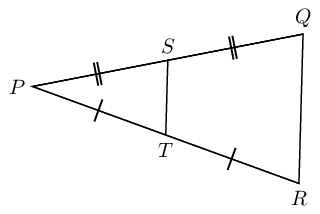

In \(\triangle PQR\), \(T\) and \(S\) are the mid-points of \(PR\) and \(PQ\) respectively. Prove \(TS \parallel RQ\).

Hint: make a construction by drawing \(SR\) and \(TQ\).

Converse: a line through the mid-point of one side of a triangle, parallel to a second side, bisects the third side.

Chapter 8: Theorem: Proportion theorem

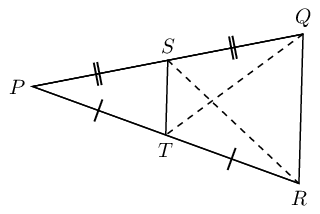

A line drawn parallel to one side of a triangle divides the other two sides of the triangle in the same proportion.

(Reason: line \(\parallel\) to one side \(\triangle\))

\(\triangle ABC\) with line \(DE\parallel BC\)

Draw \({h}_{1}\) from \(E\) perpendicular to \(AD\), and \({h}_{2}\) from \(D\) perpendicular to \(AE\).

Draw \(BE\) and \(CD\).

\begin{align*} \dfrac{\text{Area }\triangle ADE}{\text{Area }\triangle BDE} & = \dfrac{\frac{1}{2}AD.{h}_{1}}{\frac{1}{2}DB.{h}_{1}}=\dfrac{AD}{DB} \\ & \\ \dfrac{\text{Area }\triangle ADE}{\text{Area }\triangle CED} & = \dfrac{\frac{1}{2}AE.{h}_{2}}{\frac{1}{2}EC.{h}_{2}}=\dfrac{AE}{EC} \\ & \\ \text{but} \enspace \text{Area }\triangle BDE & = \text{Area }\triangle CED \quad \text{(equal }\text{base }\text{and }\text{height)} \\ & \\ \therefore \frac{\text{Area }\triangle ADE}{\text{Area }\triangle BDE} & = \frac{\text{Area }\triangle ADE}{\text{Area }\triangle CED} \\ & \\ \therefore \frac{AD}{DB} & = \frac{AE}{EC} \end{align*}Similarly, we use the same method to show that:

\[\frac{AD}{AB} = \frac{AE}{AC} \quad \text{ and } \quad \frac{AB}{BD} = \frac{AC}{CE}\]Converse: proportion theorem

If a line divides two sides of a triangle in the same proportion, then the line is parallel to the third side.

(Reason: line divides sides in prop.)

Worked example 3: Proportion theorem

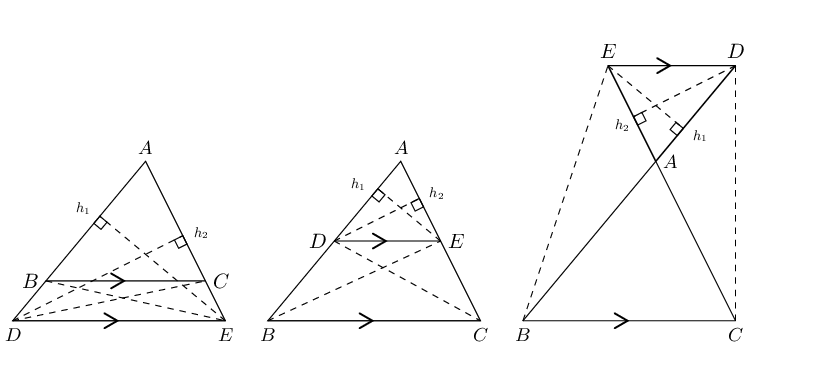

In \(\triangle TQP\), \(SR \parallel QP\), \(SQ = \text{12}\text{ cm}\) and \(RP = \text{15}\text{ cm}\). If \(TR = \frac{x}{3}\), \(TP = x\) and \(TS = y\), determine the values of \(x\) and \(y\), giving reasons.

Use the proportion theorem to determine the values of \(x\) and \(y\)

Consider \(TP\):

\[\begin{array}{rll} RP & = x - \frac{1}{3}x& \\ & & \\ & = \frac{2}{3}x &\\ & & \\ \therefore 15 & = \frac{2}{3}x& \\ & & \\ x & = \text{22,5}\text{ cm} & \\ & &\\ TR & = \frac{1}{3}(\text{22,5})& \\ & & \\ & = \text{7,5}\text{ cm} & \end{array}\]Consider \(TQ\):

\[\begin{array}{rll} \frac{TS}{SQ} & = \frac{TR}{RP} & (\text{line } \parallel \text{ one side of } \triangle) \\ & & \\ \frac{y}{12} & = \frac{\text{7,5}}{15} & \\ & & \\ \therefore y & = \text{6}\text{ cm} & \end{array}\]Special case: the mid-point theorem

A corollary of the proportion theorem is the mid-point theorem: the line joining the mid-points of two sides of a triangle is parallel to the third side and equal to half the length of the third side.

If \(AB = BD\) and \(AC = CE\), then \(BC \parallel DE\) and \(BC = \frac{1}{2}DE\).

We also know that \(\frac{AC}{CE} = \frac{AB}{BD}\).

Converse: the mid-point theorem

The line drawn from the mid-point of one side of a triangle parallel to another side, bisects the third side of the triangle.

If \(AB = BD\) and \(BC \parallel DE\), then \(AC = CE\).

Proportion theorem

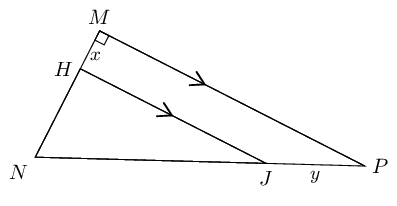

In \(\triangle MNP\), \(\hat{M} = \text{90}°\) and \(HJ \parallel MP\).

\(HN:MH = 3:1\), \(HM = x \text{ and } JP = y\).

Calculate \(JP:NP\).

Calculate \(\dfrac{\text{area } \triangle HNJ}{\text{area } \triangle MNP}\).

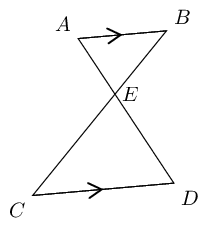

Use the given diagram to prove the Proportion Theorem.

Given: \(AB \parallel CD\)

Required to prove: \(AE:ED = BE:EC\)

Construction: Draw \(AC\) and \(BD\)

Proof: use area of \(\triangle\)'s

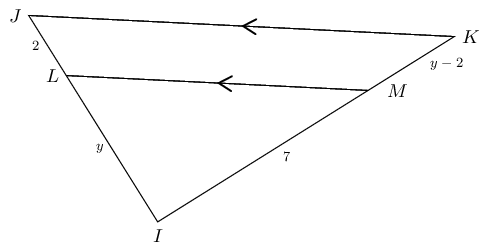

\[\begin{array}{rll} \dfrac{\triangle AEB}{\triangle ACB}&= \dfrac{EB}{CB} & (\text{same height}) \\ \dfrac{\triangle AEB}{\triangle ADB}&= \dfrac{AE}{AD} & (\text{same height}) \\ \text{But } \quad \triangle ACB &= \triangle ADB & (AB \parallel CD \enspace \therefore \text{ same height}) \\ \therefore \dfrac{EB}{CB} &= \dfrac{EA}{DA} & \\ \therefore \dfrac{EB}{CE} &= \dfrac{EA}{DE} & \end{array}\]In the diagram below, \(JL = 2, LI = y, IM =7 \text{ and } MK = y - 2.\)

If \(LM \parallel JK\), calculate \(y\) (correct to two decimal places).

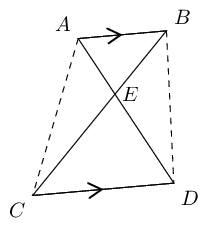

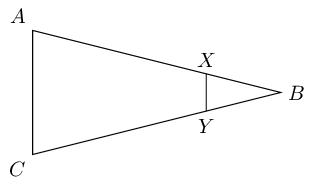

Write down the converse of the proportion theorem and illustrate with a diagram.

Converse of the proportion theorem: a line cutting two sides of a triangle proportionally will be parallel to the third side.

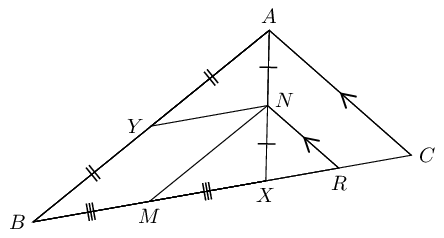

In \(\triangle ABC\), \(X\) is a point on \(BC\). \(N\) is the mid-point of \(AX\), \(Y\) is the mid-point of \(AB\) and \(M\) is the mid-point of \(BX\).

Consider \(\triangle ABX:\)

\[\begin{array}{rll} YN &\parallel BX & (Y \text{ and } N \text{ mid-points of } AB \text { and } AX ) \\ MN &\parallel BA & (M \text{ and } N \text{ mid-points of } BX \text { and } XA ) \\ \therefore YBMN &\text{ is a parallelogram} & (\text{both opp. sides } \parallel) \end{array}\]Consider \(\triangle AXC:\)

\[\begin{array}{rll} RN &\parallel CA & (\text{given}) \\ \text{And } XN &= NA & (N \text{ mid-point of } AB ) \\ \therefore XR &= RC & \\ M &\text{ is the mid-point } BX & (\text{given}) \\ \therefore MX + XR &= \frac{1}{2}BX + \frac{1}{2}XC & \\ \therefore MR &= \frac{1}{2}(BX + XC) & \\ MR &= \frac{1}{2}(BC) & \end{array}\]|

Previous

8.3 Polygons

|

Table of Contents |

Next

8.5 Similarity

|